Dr. Gilda Odera

By Dr. Gilda Odera and Annepeace Alwala

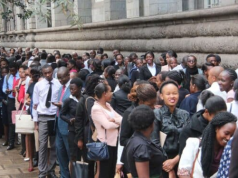

Unemployment continues to be one of Kenya’s biggest problems. For many years, governments have been keen to fix it through industrial expansion, improved market access, and policies aimed at easing the cost of doing business.

Employers, on their part, have also been urged to absorb more young people into the workforce. Yet, in spite of all these efforts, the problem persists because the world of work itself has changed, while our labour systems have not.

The honest truth is that employment models, which were solely designed for the industrial era, cannot keep up with the many young people who enter the job market each year. Factories, offices, and public service jobs simply cannot keep pace with Kenya’s high population growth and rapid technological changes.

In light of new trends where digital platforms, artificial intelligence, and new modes of service delivery have reimagined how global economies function, Kenya can no longer look away from the fact: the country needs a new social contract on labour relations-one that fits modern skills to modern work, while entrenching inclusion and fairness in the rapidly changing economy.

Africa’s demographic story makes this even more urgent. With an average age of 19 years, Sub-Saharan Africa is the youngest region in the world, and its population is expected to double by 2050.

For Kenya, this youth bulge can be a blessing or a ticking time bomb. Properly equipped, this generation could drive the next wave of innovation and growth; left behind, it could fuel deeper inequality and unrest.

Already, 70 percent of Kenya’s workforce needs reskilling to meet the demands of a modern economy. Shortages in critical skills are reported by employers even as millions of graduates remain unemployed-a paradox that points to a deeper misalignment between education, work, and economic transformation.

Part of the problem is the breakdown in social dialogue the once-strong tradition of consultation between government, employers, and workers. In place of constructive engagement, we see piecemeal policies, disputes in the courts, and siloed decision-making.

We must rebuild that dialogue. This is the only way to formulate solutions that indeed link skills to demand, modernize labour regulation, and prepare for the disruptions that technology will bring. Without this, we run the real risk of wasting precious time and resources on half-measures that do not resolve the problem at its core.

Old models of employment-manufacturing and public service jobs-cannot deliver inclusive growth. They simply cannot absorb the millions joining the labour force every year.

The future lies in emerging digital sectors that demand adaptable skills-in data, AI, and the broader platform economy-and these can be mastered through shorter, targeted learning programmes.

Kenya stands to learn from countries such as Germany, where social dialogue anchors one of the world’s most resilient labour markets.

Its Dual Training System, combining classroom instruction with hands-on industry experience, ensures that workers’ skills evolve with market needs.

Kenya has made small but impactful first steps into this. The Federation of Kenya Employers through the Dual Technical and Vocational Education and Training Programme links skills training to industry demand, with 338 already employed on real jobs out of a target of 6,000 placements countrywide by 2024.

Private sector players are also innovating: Sama, for example, has partnered with the University of Nairobi to train young Kenyans for jobs in artificial intelligence.

It’s a clear example of how the digital economy can create value at home rather than simply consuming technology built elsewhere.

The platform economy presents yet another opportunity. Estimated to generate KSh 64.5 billion every year, it is increasingly an important source of flexible income for thousands.

However, unless the new social contract extends protection and inclusion for these platform workers, this sector risks deepening inequality instead of solving it.

A modern workforce cannot thrive on outdated policies. Kenya’s new social contract for labour relations must rest on three pillars:

Trust: rebuilt through genuine dialogue among all labour stakeholders.

Shared responsibility, considering that no sector can singly reverse the unemployment situation.

Innovation: designing labour policies that protect workers while still allowing digital industries to flourish.

The skills demanded by the digital economy are within reach. With focused, practical training and clear pathways to opportunity, Kenya’s youth can be globally competitive. What’s needed now is leadership-to make collaboration, not confrontation, the foundation of our labour system.

Traditional employment models have run their course. The only way Kenya, for instance, will achieve inclusive growth in the 21st century is by embracing a new social contract for labour relations-one built for the realities of the digital age.

Dr. Gilda Odera is the National President at the Federation of Kenya Employers (FKE). Annepeace Alwala serves as the Vice President, Global Service Delivery, at Samasource Kenya.